It’s been more than two decades since ingredients and nutritional information labels were adopted for packaged food within the EU. But, even prior to this, countless producers began listing ingredients to better inform consumers as to what was in the food they were buying.

Despite initial talks in the late 1970s, alcoholic beverage producers (whether of beer, spirits or wine) have managed to avoid listing both the ingredients and nutritional information on bottle labels.

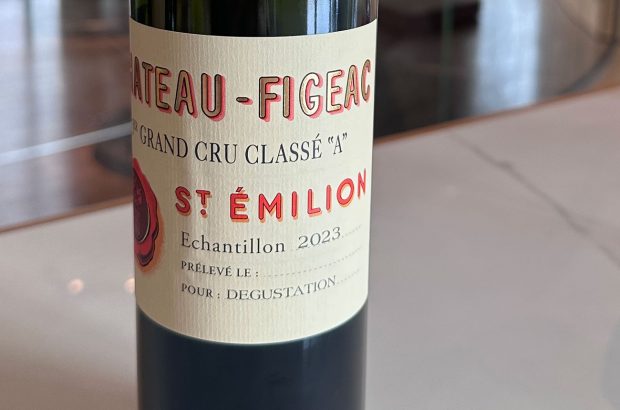

For wine, this comes to an end on 8 December 2023. Any wine sold in the EU which was produced and/or labelled from that date will be legally required to declare any ingredient added during the winemaking process (e.g. sulphur dioxide, commercial yeasts, additional sugar, acidity, colourants etc.), and which is contained in the finished wine.

Additionally, full nutritional information – as is the case for any processed food product – will need to be supplied, such as how much salt, sugar, carbohydrates and proteins are in a specific bottle of wine. The total calories in the standard Kcal/100ml format will also have to be declared.

If this is news to you, you’re not alone. A great many people in the wine trade, especially those outside the European Union, haven’t heard about the changes. The core group currently affected comprises European winemakers, who will need to have everything in place to meet the new regulations in less than five months. As this applies to any wine sold within the EU, imports from outside will have to comply as well.

Does this mean that wine labels are going to look a great deal more like a can of Coca Cola or a packet of biscuits? Yes and no, as winemakers will have greater choice in the way the information is provided.

While it will be mandatory to state the alcohol content, potential allergens, bottle size and energy value on the label, the nutritional information and ingredients can be stored online, and accessed via a QR code on the wine bottle. Where this information lives online must be devoid of all promotional material, so it simply can’t be part of an existing product page and it can’t use any data tracking methods.

Despite producers needing to list sulphur dioxide (sulphites) as an ingredient if added – as is the case in most wines – the main label will still have to state ‘contains sulphites’ if the total level in the wine is above 10mg/L.

But why is wine is being singled out for this regulation? Why not beer and spirits? It’s because despite the EU starting the legal process a decade ago, the wine industry at large has resisted voluntarily including this information on the label. For every Ridge Vineyards in California or Denis Montanar in Friuli, Italy, there are thousands who don’t state what has been added to the wine during production. In contrast to the wine industry, 70% of beer producers – as well as many spirits producers – already voluntarily add this information to their products.

From 8 December 2023, to omit or fudge the information will in effect be consumer fraud.

While consumers haven’t been confronted with these changes yet and winemakers in Europe are working to adapt to them, what about those in the wine trade who will need to communicate this to customers?

John Baum of The Winemakers Club in London, which sells an eclectic mix of wines mostly from Europe, told Decanter: ‘No, I wasn’t aware of it until now. At the moment, almost everyone in the UK market is more concerned about the impending back label additions that will create an information panel similar to the US wherein it states the importer and other information.’

Ceri Smith of Biondivino in San Francisco, which sells mostly Italian wines, said: ‘I didn’t know that these changes were coming but I’ve been saying that we’ve needed them for years. How has wine gotten away with not having this information on it?’

Victor Jiménez of La Vinícola in Barcelona, which sells wines local to the Catalan region, said: ‘Yes, I’m definitely familiar with them as I’ve been talking to producers who told me about them. For people who shop for wine in supermarkets based upon price, I don’t see that things will change that much. Honestly, how many people in general buy a packet of cookies or ketchup and pay attention to the ingredients? For the select few who do, I think this will be a very positive thing.’

These changes form the largest modification to wine labelling in over a century. Since France implemented the law for protection of origin of place in May 1919, which eventually established the appellation system in 1935, we haven’t seen this much clarity legally enforced on a bottle of wine.